The relentless pursuit of simplicity is the discipline to avoid initiatives that are not core to the mission of your business, the dedication to abstract away all complexity from the customer in achieving that mission, and continually divesting all activities that are not central to how you provide value to your customers. It’s a bias for saying no, a guideline to know when to say yes, and a call to perpetual vigilance. Adopting these practices helps maintain the essence of what makes your business unique. It frees up the resources needed to remain proficient at delivering innovative products with a sublime level of simplicity.

What an individual, team or business can do is often limited only by imagination and resources; but what it decides not to do is just as important. A relentless pursuit of simplicity is embodied by a refusal to develop a product or feature that is not directly aligned with the core mission of the business. This does not preclude experimentation. There’s value in giving teams latitude to try something new, especially in an effort to explore a new technology or way of working. However, there needs to be a bright line between when the experiment ends and commercial use begins. Hackathons and side-project time are important because they give a name to, and a time-boxed constraint for these tangential activities to exist in. Taking an experimental idea from proof of concept to viable product needs to be achieved by a series of gating functions. These serve as check points where by an agreed upon level of functionality or progress must be demonstrated, and a consensus reached as to whether, and how, to proceed. It’s during each of these checkpoints that the initiative must be openly challenged. To proceed, it must be aligned with the core mission of the business and create a point of differentiation that drives value for the customer.

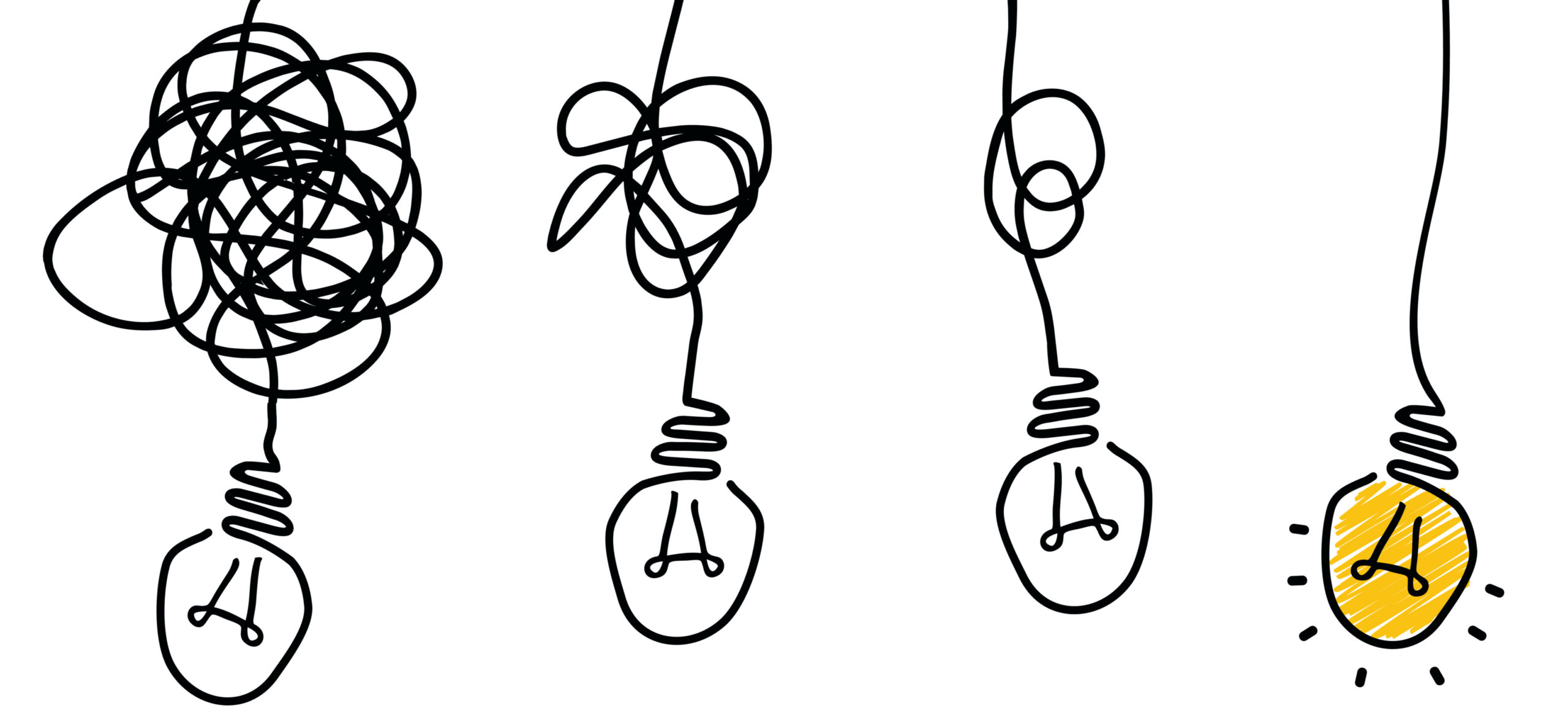

The products and features a business decided to build must abstract all complexity away from the customer. Providing the customer with simplicity is complex. It takes an enormous amount of effort to create the simplest experience. The best experience is one that improves over time to the point where it no longer exists. The best user interface truly is no user interface just as the best customer service is to not need any interaction with customer service. To relentlessly pursue simplicity is to iteratively remove more and more of the steps, the screens, the processes, until there’s nothing left. Nothing left because the users intent could be satisfied intuitively and automatically. This dedication to simplicity requires rejection emotional attachment to the current form of the product. Take for example the out-of-box setup experience of an iPhone. My team worked tirelessly release after release to polish each of those step-by-step white screens that stand between you and using your beautiful new phone. But, we knew that the best user experience would be to not go through the setup process at all! Eventually we built a setup process that allows the users settings to be migrated seamlessly from their old phone to the new phone just by putting the two devices side by side. That’s the relentless pursuit of simplicity at work: iteratively improving the user experience until it evaporates.

The relentless pursuit of simplicity helps to maintain the efficiencies needed to enable innovation and excellence. For an organization to have time to invest in exploration, a lifecycle needs to be established for the components that form the products. Deciding whether to build versus buy is part of the solution, but it’s only a point-in-time determination. Consideration has to be given to the longer term vision. A decision to build may be a necessary evil due to deficiencies in what’s available in market. That’s a problem that should resolve itself over time. These temporary elements must be constantly, relentlessly revisited with a view to replacing them with a third party offering as soon as possible. The impact of technical debt pales in comparison to the drain on resource caused by teams owning functionality that could be replaced by third party offerings. The return on the cost of replacing these components is the resources that are freed up and redirected toward improving the core elements of the product.